Gijubhai's Divaswapna

An educator's reverie

The year was 1911. A young man set up practice as a District Pleader in Vadhwan Camp, in the erstwhile princely state of Bhavnagar in Saurashtra. His practice was doing well, he was gaining a name and earning too, but his heart was not in the machinations of legal matters.

In 1913, he became a father to a son. The advent of the child Narendra triggered the life mission which would launch him into a new role. The man was Gijubhai Badheka and his mission was to bring about a revolution in the field of child development and education.

Indian education during that time was a curious mixture of the Macaulayism as practised by the English rulers and the traditional “spare the rod and spoil the child” tenet. Narendra’s parents saw the sorry state of the local schools and were apprehensive about the kind of education their son would get. Gijubhai yearned for something different for his child, but was not able to visualise what this could be. So he started reading whatever he could find about education and educators. He also started sharing his anxiety and dilemmas with his friends.

One of these was friends was Darbarshri Gopaldas Desai, who visited Vadhwan Camp often. He told Gijubhai “If you want to read literature about children’s education, and see a new kind of school, go to Vaso and meet Motibhai Amin”. This was when the door opened for him. Gijubhai went to Vaso, met Motibhai and saw his school. He came back with many books; among which was a book (Montessori Mother) describing the Montessori Method of education. This was Gijubhai’s introduction to the thinking of Maria Montessori, and her writing.

The more he read, the more deeply he started thinking about children and child development, and about putting the theory to practice. He also started experimenting with young Narendra, and sharing his observations with his friends, as also the ideas of Montessori. As his desire to spend more time and energy into this new challenge grew, the further he drifted from his legal practice.

That is where serendipity stepped in. In 1915, Gijubhai helped to frame the constitution of an educational institution in Bhavnagar called Dakshinamurti. Its founders were kindred spirits, all grappling with dilemmas about education, as well as reading the works of Montessori. This was the turning point. At the age of 32, Gijubhai quit his legal practice, and joined Dakshinamurti in 1916, initially as Assistant Warden of the student’s hostel, and teaching in the High School. His direct interactions with students reinforced his conviction that if real change had to happen – it was critical to start from early childhood. He put forth a proposal to the Board to start an experimental pre-school (Balmandir). His wish was granted and in 1920 the Daxinamurti Balmandir started. This became Gijubhai’s karmabhoomi (the land where one works). And this is where he applied the Montessori philosophy and method, drawing upon the core beliefs and tenets about child development, while adapting the methods and techniques to suit the local realities.

As he experimented with new approaches and methods, Gijubhai closely observed the responses of the children and noted these down. He also realised that his experiments with children would make be effective only if teachers and parents were to understand and apply the same in their dealings with children. And so he wrote about these addressing specifically teachers (Prathmik Shikshak) and parents (Ma Baap Thavu Aghru Chhe and Aa Te She Mathaphod).

All his experiments, observations, notings and vision for a different kind of education culminated in the book titled Divaswapna (Daydream). This is a fictional story of teacher which has close parallels with Gijubhai’s own experiences.

- Mamata Pandya

The Story of Divaswapna

Divaswapna was published in 1931 in Gujarati.

This is the fictional story of a teacher Laxmiram, as related by himself. The book is almost like a journal that traces his experiences of teaching in one year.

It is set in a time when the British were ruling India. Education was bound by a prescribed curriculum, belief in corporal punishment, and supervised by white Education Officers.

Laxmiram a young and idealistic teacher with very different ideas about what good education can be, approaches the Education Officer for an opportunity to teach in a school and put some of his theories into practise.

The Education officer at first laughs at him, but then reluctantly gives him permission to teach class 4 for one year. But with the condition that at the end of the year the students would take the same examination as the rest and show good results.

Laxmiram takes up challenge. Armed with all his theories and academic reading he enters class 4. He is shocked to finds that it is like a fish market - with rowdy students screaming, running around and fighting. He realises that to make his daydream into a reality he would have to find ways to reach the hearts of the students.

The next day he starts by telling them a story. The class becomes quiet and attentive. In fact they are reluctant to go home. The stories continue for the next ten days. When he is reprimanded for this, and not for not following the curriculum he explains:

I am teaching them orderly behaviour through story sessions. They are being motivated. I am exposing them to literature and linguistic skills.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 12)

This initiation leads the students to want read, they begin to perform the stories, and share them. Laxmiram sets up a small class library. Students who have never read anything other than their textbook, are curious and interested.

Laxmiram begins to use games as a way to instil the concept of rules, discipline and team work.

His bigger challenge comes when he has to convince parents to send their children to school in clean clothes, with neat hair and clipped nails. Both educational authorities and parents deride him saying that personal hygiene was none of his business. But Laxmiram feels that the first lesson to be learnt was neatness, cleanliness, and order. And he introduces daily routines in the class to inculcate these habits.

Laximram is a teacher with passion, ideals and zeal to try something different. But he faces derision and innumerable challenges from all quarters.

He has an uphill task not just in handling the students, but equally in meeting the expectations of the parents.

It is necessary for the teacher to guide the child without letting him feel the pressure too much, so that she may be always ready to supply the desired help but may never be the obstacle between the child and his experience.

I had believed that giving a talk and a little explanation to parents would suffice. But the parents here know only one thing. "Teach the boys" they say. They don’t have time even to listen to anything else and they don't understand either.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 25)

His colleagues look upon him as a misguided individual.

My colleagues the teachers have no faith in me. They look down upon me as an out and out impractical person. Maybe I am rather. Besides I have no experience. But I have no faith in their beliefs and methods of teaching. They annoy me. …The other teachers say that I am spoiling the boys by overindulgence; they complain that I tell the boys stories only and don’t teach them, that I make them miss their classes by taking them out for games.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 26)

The higher authorities want quick results.

The Education Officer has now become rather impatient. He has his own problems. He has to contend with his superiors and opponents. He wants to share the glory and therefore want results but he wants them quickly. He has his limitations in helping me.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 26)

Laxmiram is battered, but not beaten. He resolutely clings on to his convictions and continues his experiments.

I am sure mine is the right approach. We shall see. These games and stories are, to my mind, half their education. I will have to bear in mind that my task is going to be difficult, and I should not lose sight of this.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 26)

These efforts go on for the first three months. In the third month, Laxmiram starts looking at the prescribed syllabus, knowing that the students would have to pass exams in all the subjects. While adhering broadly to the content, Laxmiram adopts innovative methods to tackle the syllabus. He introduces dictation from storybooks to develop language skills; history through stories; spontaneous play-acting instead of rote learning and recitation; grammar through word games; language through riddles and puzzles; geography and nature study through field trips and outings. He engages the students in what we, today, call “learning by doing.”

As the year goes on, Laxmiram continues to try new approaches to teaching different subjects. His students do well in the terminal exams. Some of the teachers too begin to see that changes are possible, but most of them are still sceptical. Their perception is that Laxmiram can afford to do these experiments because he does not have to worry about money; and that he reads English books from where he gets his ideas, and that he has the time and leisure for such things. Laxmiram refutes this.

Experiments do not succeed merely because one knows English. That is a lame excuse one resorts to when one doesn’t want to work. The main thing is the intuition to innovate. And that comes from the yearning of ones soul for a cause.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 88)

At the end of the academic year the Education Officer sees real change in the students of Class 4. Not just in their academic performance, but equally in their appearance and behaviour. He recommends that the entire class be promoted. But Laxmiram himself recommends otherwise in the case of a few students who he feels had not come up to the mark. And for this he blames not the students but the system.

It is not that they are unfit for the school. Rather this school is unfit for them. The school is unable to teach them what they have an aptitude for.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 102)

In a break from tradition, it is decided that the prize money of Rs 125 which every year was distributed among the bright students was instead to be used for starting a school library, and this would be continued every year.

At the Annual Day function the Education Officer concludes by saying,

When this gentleman came to me last year with the request for permission to make an experiment in Class 4 of the primary school, I considered him to be an impractical fool. I had thought that he was just like many others of his kind and would run away at the first opportunity when put to the test. So I gave him permission. I had no faith in him. But I must admit he has achieved success in his experiment. He has changed my ideas. …Look at the children of his class. How orderly, healthy and cheerful they are. I am a witness to their development and growth. Their parents have often expressed their satisfaction to me.

Divaswapna - Gijubhai Badheka (Translation - Chittaranjan Pathak, N.B.T. 2006) (p 104)

Lakshmishankar concludes, "The Director's speech was over. Everyone dispersed and I came home."

And thus an educator's reverie bears real fruit.

Divaswapna An Educator's Reverie is considered as a seminal contribution to world-class pedagogy in the last century. It was originally published in 1931 in Gujarati. In 1990 it was published in English by the National Book Trust. It has subsequently been published by NBT in 11 Indian languages.

Publishing Divaswapna

Sharing the dream in many languages

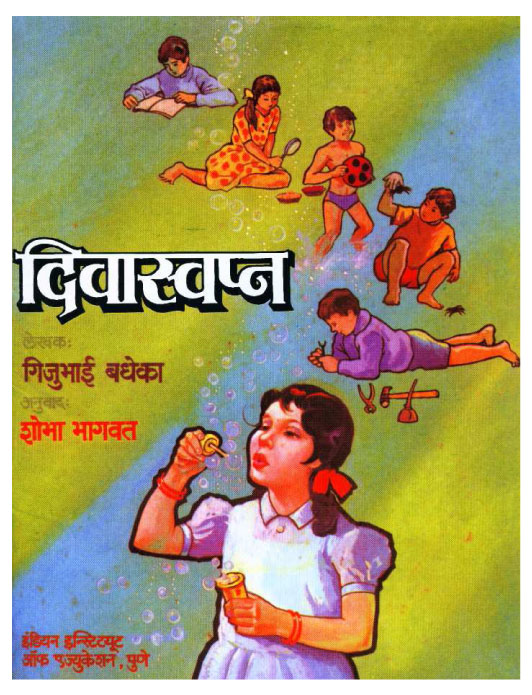

An educational magazine Naya Shiksak (published by the Education Department, Rajasthan) first reprinted in the 1980s the whole Divaswapna in Hindi as a special issue of their magazine. The book was translated from Gujarati into Hindi by Kashinath Trivedi (Dada) a few years after it came in Gujarati. But Kashinathji failed to find a publisher in Hindi. Later he printed 1000 copies in Hindi with his own money. Kashinathji (Dada) was an eminent Gandhian and also the first minister of Education of Madhya Pradesh. This is what he recounted. "I always carried a few copies of Divaswapna in my bag. Whenever he met someone interested in Education, I always told him the story of Divaswapna and if the person was interested in reading it sell it for Rs 1.25." This is how without any institutional support Dada kept Diwaswapna alive for over 50 years!

I was simply swept away after reading Divaswapna. It was the most original and creative Indian experience of a school which I ever read. So, reaching Divaswapna out to other people became a personal obsession.

Shobha Bhagwat, founder Director of the Garware Balbhavan, Pune translated Divaswapna in Marathi. But we could not find a publisher! "If it is prescribed in the BEd course then we will publish it," the publishers told us.

Anil Bordia - Secretary Ministry of Human Resources Development had read Divaswapna and he loved it. He helped us by giving a grant to the Indian Institute of Education (IIE, Pune) headed by Dr. Chitra Naik to publish it in Marathi. The first print run in Marathi was 35,000 copies!

I sent a copy of the Hindi Divaswapna to Shanta Rameshwar Rao, founder of the Vidyaranya School, Hyderabad and the wife of the Chairperson of Orient Longman. Shanta understood Hindi but was not fluent in reading it. She came to Vidyaranya early for a fortnight and had the Hindi teacher read it aloud to her. Later she wrote to me "Having not read Divaswapna earlier I have no right to call myself an educationist!"

We thought that Divaswapna should be translated into English from the original Gujarati. Then we discovered Chitaranjan Bhai Pathak who had just retired as a principal of a school in Mumbai. He was also Gijubhai's son-in-law. The Hyderabad Book Trust published it first in Telugu and it was published in Malayalam by the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad.

Anil Bordia, secretary MHRD gave a copy of Divaswapna to Arvind Kumar - Director of the National Book Trust (NBT) to read and if he found the book worthy to publish it in Indian languages. Arvind Kumar loved it. "Who should write the foreword?" he asked. I suggested the name of Prof. Krishna Kumar – the best Indian educationist. NBT has published Divaswapna in many Indian languages. Today Divaswapna has become a must read for all teachers. This in short is the story of the resurrection of Divaswapna – India's most creative contribution to education in the last century.

- Arvind Gupta